Chi is one of the most debated topics in martial arts. At its simplest, some teachers describe it as nothing more than controlling your breathing. At the other extreme, others claim Chi grants them the ability to perform feats like “no-touch knockouts” or even channel mystical powers. But where does the truth actually lie? Let’s start with a definition.

At its core, Chi is often defined as “life force energy”—the vital energy that sustains life. Different cultures use different names: in China it’s Chi (or Qi), in Japan it’s Ki, and in India it’s known as Prana. Beyond martial arts, it has long been part of spiritual and healing practices, making the connection between body, mind, and spirit closer than many might first assume.

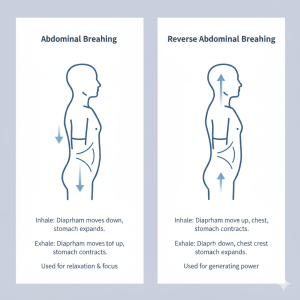

When it comes to martial arts, Chi is most commonly expressed through breathing methods. Different breathing patterns can produce different results. The two most common are abdominal breathing and reverse abdominal breathing.

-

In abdominal breathing, the stomach expands on inhalation while the chest sinks. This is often used for relaxation and focus.

-

In reverse abdominal breathing, the chest expands and the stomach contracts. This creates internal pressure and is typically associated with generating power.

Chart of Abdominal vs Reverse Abdominal breathing.

In my own training, I use abdominal breathing to calm the body and mind, and reverse abdominal breathing to generate strength. In fact, most people naturally switch to reverse abdominal breathing without realizing it. For example, when lifting something heavy or trying to push a stalled car, your body almost automatically engages this type of breathing—even if you’ve never trained in Chi Kung (Qigong).

Chi in Religious and Spiritual Practices

While my focus is martial arts, it’s important to understand that Chi is not limited to fighting or training. Many religious and spiritual traditions also incorporate breathing and energy concepts, though they approach them with different goals in mind.

In Daoism, Chi (Qi) is seen as the natural energy of the universe. Breathing exercises, meditation, and gentle movements (such as Tai Chi and Qigong) are used not only for health but also for spiritual alignment with the Dao, or “the way of nature.”

In Indian traditions, the concept of Prana is central. Breathing practices called Pranayama are designed to control and direct life force energy. These are often used in yoga and meditation to achieve clarity, balance, and spiritual growth.

In Japanese culture, Ki is integrated into practices like Aikido and Reiki. In Aikido, Ki is about harmonizing energy with an opponent rather than clashing against it. Reiki, meanwhile, uses the concept of Ki as a form of spiritual healing through touch.

What ties all of these together is the use of breathing as a bridge between body, mind, and spirit. Whether the goal is healing, meditation, or spiritual enlightenment, breath control is the universal method of cultivating Chi.

From a martial artist’s perspective, we don’t need to dive deep into the theology to appreciate the overlap. The same breathing that helps a monk calm his mind for meditation can also help a fighter steady his nerves before stepping into the ring.

Chi Kung practiced as a moving martial art or a meditation

A Personal Story of Survival

One of the most powerful Chi Kung stories I know isn’t about breaking bricks or knocking someone down without touching them—it’s about survival.

When I was 18, I moved to a new city and went searching for a place to train. Along the way, I met someone who practiced shamanism, and we quickly became friends, sharing ideas on meditation. One day, when he took off his shirt, I noticed his chest was completely caved in. Naturally, I had to ask what had happened.

He told me that years earlier, he had been caught in the middle of a gas station robbery. In the chaos, he was shot in the chest with a shotgun. My first reaction was, “How on earth did you survive that?”

His answer shocked me. He explained that, after being shot, he stood up, pressed his hand firmly against his chest, and told the gunman, “I’m not calling the cops. I just want to walk to the hospital and get help.” Amazingly, the robber let him go.

The nearest hospital was about half a mile away, and he was losing blood fast. To keep himself alive, he said he relied on something he called “The Rain Cloud Meditation.” In this practice, he imagined his life energy (known in some traditions as the Hara or Dan Tian) rising up through his body to the crown of his head, then “raining” back down.

In Kung Fu, I had learned a variation of this called the Small Orbit Meditation—a technique where energy is visualized as circulating throughout the body. The method was different in imagery, but the principle was the same: controlled breath, calm focus, and directing energy inward.

Did Chi magically save his life? No. The more likely explanation is that pressing his hand to his chest slowed the bleeding, while the meditation helped him control panic and keep his heart rate low. A slower heartbeat meant less blood loss, giving him the time he needed to reach medical help.

Fortunately, the doctors in his area were skilled enough not only to save him, but to restore full functionality. Aside from the scar and the caved-in chest, he had no lasting disabilities or health problems.

To me, this story illustrates the true power of Chi practice. It isn’t about supernatural miracles. It’s about how breathing, focus, and mental discipline can make the difference between life and death. In this case, Chi practice helped him survive long enough for science and medicine to do the rest.

Eastern vs Western Medicine

This is the practical side of Chi — breathing, focus, and mental discipline that produce measurable, life-saving results. But Chi also lives in a different conversation: the idea of invisible energies around us — forces we can’t see but that clearly affect the world. In Part 2 I’ll compare Chi to other invisible energies (like electricity, radio waves, and sound), show how those comparisons help us understand what Chi might be, and give simple experiments and drills you can try yourself. If you thought this first post raised more questions than answers, good — we’re just getting started.